BODYBUILDING AND FAT LOSS Q&A WITH SEAN NALEWANYJ: PART 3

Alright, it’s time for Part 3 of my complete Bodybuilding And Fat Loss Q&A series.

I’ve received a lot of positive feedback on these articles so far, and I’m really glad that you guys have been finding the information helpful.

If you missed any of the previous installments, you can access them here:

Let’s dive into today’s questions…

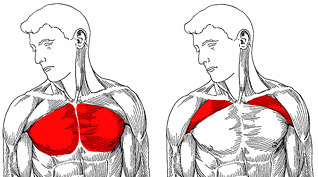

Q: Is it possible to specifically isolate different areas of the chest, such as the inner/outer and upper/lower? If so, how?

A: To a degree, yes. By using different angles and elbow positioning, it is possible to specifically shift the emphasis between the upper, middle and lower regions of the chest.

The pec major is actually made up of two different sets of fibers that have their own separate nerve innervations and fiber angles: the upper clavicular fibers (the “upper” chest) and the lower sternocostal fibers (the “mid” and “lower” chest).

Performing your pressing and fly exercises at an incline angle (around 30-40 degrees) will place more stress on the upper fibers, while using a flat or decline angle (also around 30-40 degrees) will place more stress on the middle and lower fibers, with the emphasis increasingly shifting from the middle to lower area as the decline increases.

To optimally train the upper chest, go with an incline dumbbell press and/or an incline cable fly, and for the middle/lower chest, go with a flat/decline dumbbell press and/or a flat/decline cable fly.

The cable flys can be done laying on a bench placed inside of a cable stand, or in a standing position either pulling from high to low (decline), straight across (flat) or low to high (incline).

In terms of targeting the inner and outer portion of the pecs, however, this unfortunately just isn’t possible. This is because when one strand of fibers contract along the pec muscle, the entire fiber as a whole contracts.

So, it really doesn’t matter which exercises, angles or elbow positions you use; if you want to stress the “inner pecs” or the “outer pecs”, the opposite side of those fibers must also contract as well.

Q: I’m training hard in the gym and am consistently getting stronger every week, but I haven’t made any real gains in overall body weight or muscle size. What’s going on?

A: Assuming you’re following a standard bodybuilding-style program that has you hitting each individual muscle group at least once per week and with a sufficient amount of total volume and intensity, the absence of measurable body weight increases or muscle growth is a simple issue of improper diet.

To put it simply, you’re just not eating enough.

See, your body can actually gain strength via other pathways besides just increasing the size of the muscles themselves. It also gains strength through what are called “neural adaptations”, meaning that it becomes more efficient at recruiting motor units and making use of the muscle that you already possess.

If you’re consistently gaining strength without the size, this is what’s actually going on. And the reason why this is the only adaptation you’re experiencing is because you’re not providing your body with the excess calories that are required to actually synthesize new lean tissue.

In order to gain new muscle size, you must create a calorie surplus by consuming more calories than you burn. If you’re simply eating at or around your calorie maintenance level each day (where energy consumed is equal to energy burned), your body will still gain strength through those neural pathways, but it won’t be physically able to build any considerable amount of new muscle mass.

So, the simple solution is to increase your overall daily calorie intake until you begin seeing consistent increases in overall body weight, with around 0.5-1 pound per week being a good guideline to aim for.

If you want a very basic way to calculate this, first take your body weight and multiply it by 14-16 to find your calorie maintenance level (select the lower or higher end depending on your activity level), and then add 350 calories to that number in order to create a small calorie surplus to aim for each day.

You can put as much effort into your weight training plan as you want, but if you aren’t at least roughly landing in the proper calorie range for yourself each day, you quite simply are not going to make any noticeable muscle building progress.

Q: Are lifting straps a useful training tool, or are they simply a “crutch” that would be best avoided?

A: Assuming that your underlying training goal is to alter your body composition and maximize muscle growth and/or fat loss, then lifting straps definitely can be a useful tool depending on the situation.

Putting aside the nonsense that “real men don’t use straps” or whatever else those who take weight training entirely too seriously might say, lifting straps have two primary uses in your program…

The first is for heavy compound exercises where you simply don’t possess the grip strength to hold onto the weight for the entire set, such as deadlifts or shrugs.

In this situation lifting straps are a must, otherwise you’ll be hugely minimizing the stimulation of the actual targeted muscle groups and will simply be giving yourself a really good forearm workout.

In this case you can work on your grip strength separately until it catches up, and use straps in the meantime to ensure that it’s your back, legs or whatever other muscle you’re trying to target that’s being maximally stimulated rather than your forearms. (Or, if you truly don’t care at all about developing grip strength, feel free to just use the straps indefinitely – it’s completely your choice.)

The second situation is optional, and that is to use lifting straps as a means of improving the activation of your lats and mid-back muscles during your compound upper body pulling exercises.

Straps help to eliminate your grip from the equation so that you can place all of your focus on pulling the weight through your elbows, which is a key way to shift the emphasis onto your back muscles as opposed to your forearms and biceps.

If you’re like me and find straps to be particularly helpful in this area, then they’re definitely worth using during your back workouts as a means of improving muscle stimulation and growth.

It really just comes down to your individual training goals and how much value you place on grip strength in comparison to overall muscle growth.

Also keep in mind that if grip strength really is a big concern for you, you can simply incorporate separate grip and forearm training into your workouts to take care of that.

Q: Should overall calorie intake be decreased on non-workout days in comparison to workout days?

A: Constantly cycling your calories by increasing intake on training days and reducing intake on non-training days is really nothing more than a great way to unnecessarily over-complicate your eating plan and make things harder on yourself in the big picture.

I feel like a broken record in saying this, but proper muscle building and fat burning nutrition is all about the long-term and is not going to be measurably affected by a few hundred calories more or less in small blocks of 24 hours.

We tend to categorize things in terms of individual days simply because it’s a convenient way to organize our time, but there’s really nothing special about that particular time frame, and it would be more useful to think about your food intake over longer spans of time, such as one week.

On top of that, muscle growth and fat loss are not “on/off” switches where you’re simply building muscle one day and maintaining it the next, or losing fat one day and maintaining your fat stores the next.

Instead, your body is in a constant state of both muscle growth and muscle breakdown, as well as fat burning and fat storage.

For that reason, trying to time your calories from day to day to specifically fuel each process is really just a waste of effort, and it may actually increase your chances for long-term failure by making your diet harder to stick to.

Q: Are behind-the-neck presses and pulldowns safe and effective for training the shoulders and lats?

A: Although it’s certainly possible that you could consistently perform these two exercises over the long term without ever getting injured, I don’t see any good reason to take the risk.

Vertically pressing and pulling heavy objects behind the head is simply not a natural movement pattern for the human body, as it places the shoulders into an excessively externally rotated position that overly stretches the rotator cuff (specifically the subscapularis) and significantly increases its chances for injury.

Not only that, but it promotes bad motor patterning by encouraging forward head posture (which can lead to mid/lower back problems down the line) and can also place excessive stress on the spine in those with poor flexibility.

A behind the neck press or pulldown may feel like it’s giving you a great shoulder or lat workout, but you’ll be able to stimulate these muscles just as effectively by pressing or pulling to the front and while placing far less stress on your shoulder joints and spine in the process.

There’s really no unique muscle building advantage to performing these movements behind the neck as opposed to in front, so the risk/reward factor just doesn’t make any sense at all in my view.

For the shoulders, stick to a basic seated overhead dumbbell press or military press, and for the lats, go with basic lat pulldowns with the bar coming down to your upper chest.

Thanks for the continued readership and support, and I hope these answers were informative. Part 4 is on the way soon, so stay tuned.

If you found this article helpful, make sure to sign up for your FREE custom fitness plan below...