HOW TO ELIMINATE KNEE PAIN DURING SQUATS (8 TIPS)

Nothing ruins the joy of working out more than nagging joint pain.

Not only is it physically uncomfortable, but it often stalls progression by preventing you from training at peak performance.

The knee joint is an area that very commonly acts up in many trainees, especially during the squat.

However, squats are not inherently dangerous. In fact, when performed with proper technique, they can actually strengthen the knees and reduce the risk of future injuries.

But what should you do if you experience knee pain during squats?

In this post I’ll be going over 8 tips you can implement to treat the underlying causes, eliminate the discomfort and get back on the road to squatting pain-free.

Squats & Knee Pain: 8 Tips To Follow

#1 – Do A Proper Warm Up

This is the first and most basic place to start if you’re experiencing knee pain while squatting.

Doing nothing more than one or two quick warm up sets and then jumping straight into the heavy weights is not enough if you truly want to minimize the strain on your knees and optimize training performance.

A properly executed warm up will lubricate the joints with synovial fluid, improve mobility and activate your central nervous system for greater strength, power, and faster reaction time.

#2 – Spread Your Knees Outward

A big problem many lifters run into during the squat is having their knees buckle inward.

We call this a “knee valgus,” and it’s a very common cause of knee pain from squats.

Knee valgus increases the tension on the knee joint and places a lot of stress on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), potentially leading to patellofemoral pain syndrome or even ligament tears.

The first step in preventing this is to simply be aware of what your knees are doing during the squat and to ensure that they remain in line with your feet rather than collapsing inward.

A useful cue for this is to focus on “spreading the floor apart” with your feet.

Adopting a squatting stance with your toes pointed slightly outward helps as well.

If simply adjusting your form doesn’t take care of it completely, there could be other underlying issues at play.

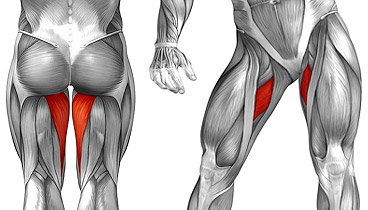

One of the most common reasons behind inward collapsing knees are weak and inactive glutes.

When the glutes don’t fire properly during a squat, they’re unable to resist the inward force your upper legs undergo during the lift, causing your knees to buckle.

Performing some very light “pre-activation” work for the glutes prior to your squatting sessions can be helpful here, as can directly training the glutes using movements such as hip thrusts and banded sidewalks.

Another helpful tip is to squat with a mini-band wrapped your knees, as this will increase the strength and activation of the glutes and force you to keep your knees spread outward throughout the exercise.

Another common cause of knee valgus is tight ankles.

Insufficient ankle mobility will pull your feet inward when you reach the lower part of a squat. Once this happens, your knees will follow automatically.

Lifters who are limited by their ankle flexibility can self-myofascial release the tissues in the calves, ankles and feet in order to loosen things up and improve ankle mobility. A lacrosse ball or other SMR tool can be used for this. (This video covers some techniques you might find helpful.)

Lastly, knee valgus can often be fixed by simply re-learning the squat using lighter loads.

Focus on keeping your knees in the proper position and getting those glutes to fire consistently, and then gradually begin adding weight again while maintaining the correct form.

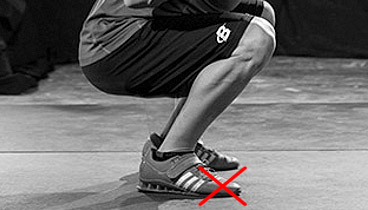

#3 – Stop Pushing Through Your Toes

When you push through your toes during the squat (or on any compound quad exercise such as leg presses, lunges, or deadlifts), you shift the tension forward and direct more stress onto the knees.

Instead, make sure to evenly distribute the weight over your entire foot.

One form cue that will help out with this is to think about “sitting back” as you descend on each rep.

Box squats are a very helpful exercise to learn how to do this correctly.

Since you can maintain a more upright shin angle with this variation, lifters with beaten up knees will often feel less pain on the box squat in comparison to regular squats.

Don’t push your hips too far back though, since this will create greater flexion at the hip joint.

When overdone, this can turn your squat into a good morning exercise and lead to more stress on your lower back.

Find a middle ground here between sitting back during the squat but without allowing your torso to collapse forward.

This will help to prevent knee pain during squats and keep your lower back protected as well.

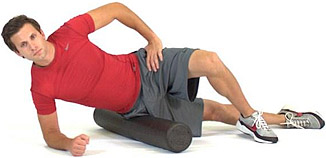

#4 – Self-Myofascial Release Your IT Band

The Iliotibial Tract (IT) band is a thick strip of connective tissue that is attached to your knee joint. It helps abduct and laterally rotate the hip and is essential for the stabilization of your knees.

However, squatting (and running) regularly can cause the IT band to become excessively tight, which pulls and creates tension on the knee joint.

While a deep tissue massage from a skilled practitioner would be ideal, self-myofascial release techniques (SMR) are a good alternative to relax those overly contracted muscles and release built-up trigger points.

The most well-known SMR technique is foam rolling.

Simply place a foam roller between your body and the ground and apply pressure to the area you’re trying to treat by slowly rolling back and forth.

Here’s how you can SMR your IT band:

Once you’ve gotten into position, perform long, slow rolls running from your hip all the way down to just above your knee. If you find an area that is particularly tender, stay on that spot for a bit longer until the pain subsides.

You’ll likely find this very painful if it’s your first time, but the discomfort will gradually decrease with repeated sessions.

#5 – Self-Myofascial Release Your Adductors

The adductors are a group of muscles located at your inner thigh.

Their primary function is to bring your legs toward the midline of your body. Aside from that, they also assist with hip flexion, hip extension and hip rotation.

The problem?

The adductors muscles – just like your IT band – have a tendency to become overly tight.

Tight adductors can increase your risk of knee pain on squats by contributing to knee valgus as discussed above, as well as by preventing proper stabilization of the femur.

You can use a foam roller for this as well along the inner portion of your thigh.

#6 – Use A Pair Of Knee Sleeves

Knee sleeves are made up of a thin layer of rubber or neoprene and are wrapped around your knees during the squat.

They help to lubricate the joints by trapping in heat, as well as providing additional support to the knees throughout the lift.

Knee sleeves should not be used as a “crutch” for bad form, and they certainly aren’t a solution to knee pain during squats in and of themselves.

However, if you’re squatting with proper form and are working on fixing some of the potential underlying issues addressed above, knee sleeves can be used (at least temporarily) to provide a bit of extra support.

#7 – Squat Deeper

Although it may seem counter-intuitive, squatting with a deeper range of motion may actually be superior for knee health.

One analysis found that full squats produce less stress on the knee joint and have a lower risk of injury than partial squats. (1)

The researchers also found that the highest force on your knees during a squat is when your upper legs are parallel to the floor.

In addition, full squats force you to use a lighter weight which not only reduces the stress on the knee joints but also on the lower back as well.

#8 – Do Front Squats

If you’ve tried all of the tips above and that stubborn knee while squatting still won’t subside, another option is to take a break from regular back squats and try performing front squats instead.

Despite the fact that front squats cause more forward knee travel, they produce less stress on your knee joint overall and may be better for long-term knee health. (2)

They’re much easier on the lower back as well.

Here is what the researchers concluded in the study linked above:

“The front squat was as effective as the back squat in terms of overall muscle recruitment, with significantly fewer compressive forces and extensor moments. The results suggest that front squats may be advantageous compared with back squats for individuals with knee problems such as meniscus tears, and for long-term joint health.”

If front squats aren’t doing the trick either, then you’ll probably just be best to take a break from squatting movements altogether to give your knees a chance to heal.

Try replacing them with another compound leg exercise such as a leg press if you find it more comfortable. Going with a lighter weight/higher rep approach would probably be helpful as well.

Squats & Knee Pain: The Bottom Line

There are many benefits to squats, but you can’t do them if you’re injured.

Conversely, it’s been a long-held belief that squats are bad for your knees. However, when performed properly, squats are the single most productive lower body exercise available and are safe on the knees as well.

In fact, they can even improve the health of your knees joints and prevent future knee injuries as long as your technique is on point.

If you’ve been experiencing nagging knee pain on squats (or just want to minimize knee strain during the exercise to prevent future injuries), implementing the 8 tips above should take care of the issue for you.

Read more about leg extension knee pain to protect your joints in that exercise, too.

If you found this article helpful, make sure to sign up for your FREE custom fitness plan below...